The effect of one ‘harmless’ story

The way migrants and refugees are portrayed in the media plays a critical role in shaping societal perception and political response. Media narratives do not just reflect public opinion – they help create it. Through repeated headlines, imagery, and story framing, media outlets construct simplified portrayals of migrants as either threats, burdens, or passive victims. These portrayals affect how the public understands migration, reinforcing fear and “otherness” in political debates and everyday interactions, which can then justify restrictive policies.

Framing is powerful because it simplifies complex realities. But when used irresponsibly or without input from those directly affected, it can reinforce stereotypes, dehumanize individuals, and shape migration as a “crisis” rather than a human experience. This makes it harder to imagine inclusive and just responses.

For example, metaphors like “floods” or “waves” of migrants suggest chaos and loss of control, which fuel public anxiety. In contrast, a more humanized, complex narrative - one that includes migrant voices - is still rare across European media landscapes.

“Listen to me, and do not hear about me”

The impact on perception and policy

Studies show that media coverage significantly impacts public perception and policy. Negative media frames lead to increased anti-immigrant sentiments and policy shifts. Right-wing parties often benefit from these narratives, and empathy drops when these parties use language emphasizing crime, illegality, and cultural difference. Positive or balanced portrayals of migrants and refugees are far less common, contributing to a cycle where marginalised voices are left out of their own stories. Media can either distort or clarify realities, depending on how migration is framed. Some misconceptions that are boosted by the media are the following:

“We only make the news when bad things happen. When someone is killed, raped or kidnapped, or when someone scammed the belasting. That’s when we’ll make the news. ”

Misrepresentations and myths

Stereotypical and polarising representations of migrants in the Dutch media do not just shape opinion, they reinforce prejudice, fuel fear, and enable social exclusion. Media narratives often strip migrants of their individuality, humanity, and agency and constructs them as either a burden or a threat. This framing creates fertile ground for myths that dominate political discourse and public debate.

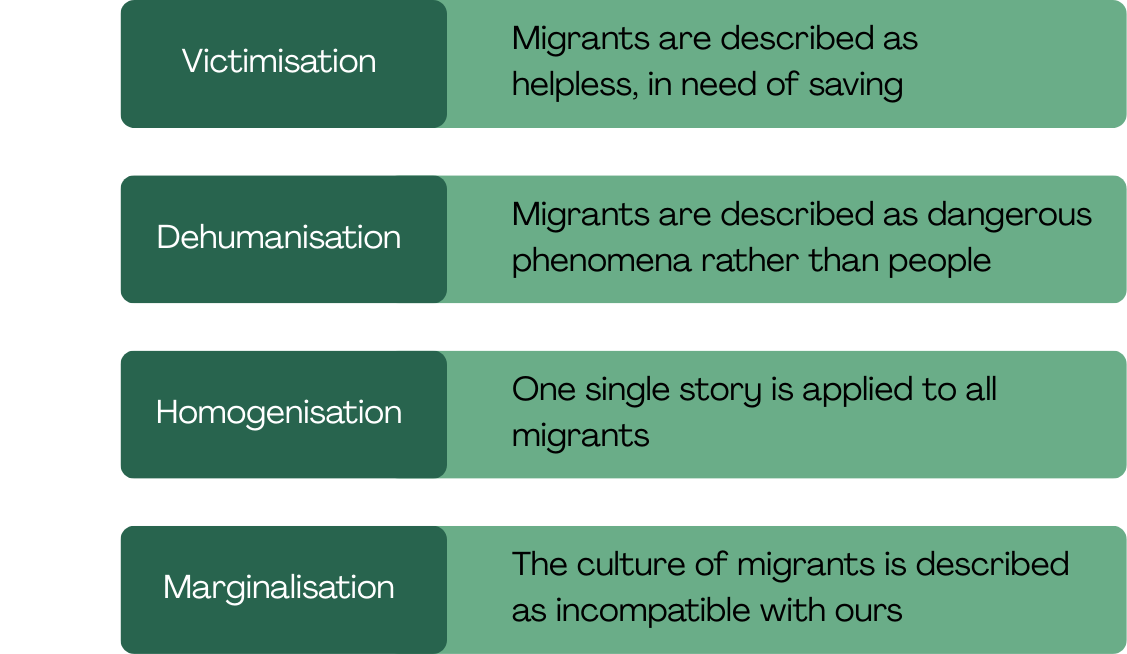

A critical analysis of media coverage and research has shown four main narratives to be wary of:

The first one is victimisation, which frames migrants primarily as helpless, suffering, poor, and desperate people in need of saving. While this might seem sympathetic, it denies them agency and reinforces a hierarchical view of "us" as rescuers and "them" as passive recipients.

Second is dehumanisation, which occurs when migrants are portrayed as criminals, terrorists, or invaders. They are described using dehumanising metaphors like "floods" or "waves," and discussed in terms of numbers rather than names. This reduces them to an abstract threat rather than real people with lives and families.

The third main narrative is homogenisation, which flattens the rich diversity of migrants and their experiences into a single story. Migrants are rarely shown as individuals with professions, histories, and aspirations. Instead, they are lumped together as an anonymous, unskilled mass. Media coverage often ignores their age, gender, education level, and cultural background.

Lastly, marginalisation portrays the culture and values of migrants as a danger to Dutch society. Instead of fostering dialogue or integration, the media often emphasises cultural incompatibility, framing migrants as outsiders who threaten the national identity.

“People think refugees come here for money or a better life, but I would give anything to go back to my old life if it meant safety. I didn’t choose this — it happened to me”

Critical media checklist

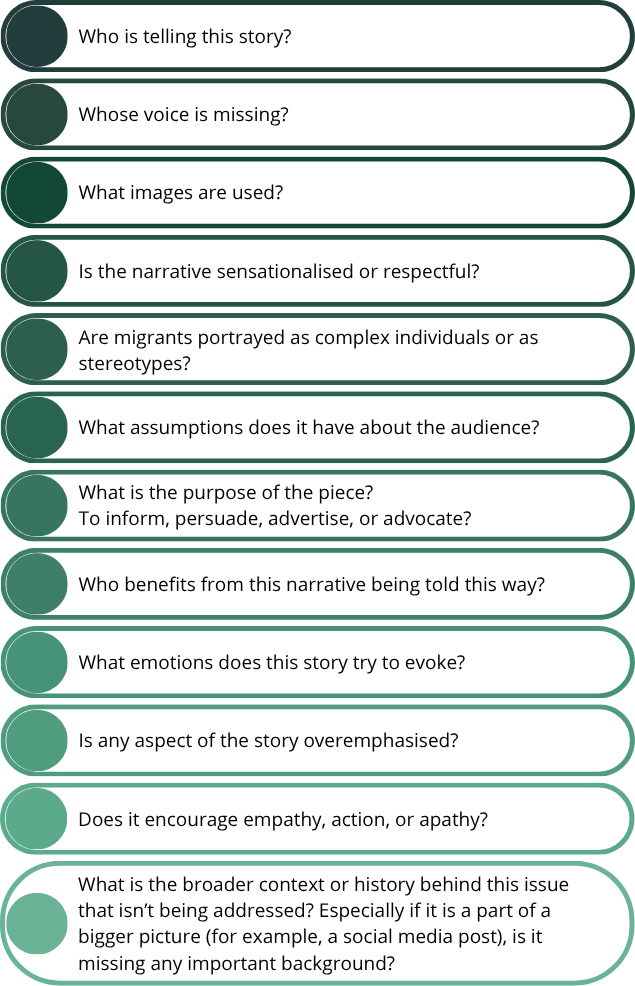

When reading news or posts, it can sometimes be difficult to notice misrepresentations and myths. By analysing media practices, the research conducted for the Justice & Peace project inspired a list of questions to ask yourself to help analyse news stories and identify bias. Ask these questions to yourself when reading the news and engaging in media. This will help you to go beyond surface-level narratives and become a more mindful, critical, and informed consumer.

How to change the narrative

Journalism is a tool that can promote democracy, truthful information, and serve the public interest. However, due to myths, stereotypes, and sensationalisation, the media often become platforms that dehumanise, polarise, and misinform. Disinformation targets migrants, portraying false narratives about their life stories. This represents a threat to social cohesion, prosperity, and individual and collective identity. Public fears, pre-existing socioeconomic inequalities, and unsubstantiated stereotypes can easily be fuelled and exploited to distort complex realities further. To counteract this, it is important that journalists, media professionals, educators, and readers take conscious steps:

Adopt a rights-based approach to migration coverage: centre the voices and lived experiences of refugees and migrants. Challenge false framings of migration as a “crisis” or “invasion.”

Expose myths through identifying and debunking misleading tropes: migrants are not “stealing jobs,” “bringing disease,” or “eroding national identity.” These claims lack factual support and are socially harmful.

Diversify sources and voices, making storytelling more inclusive: Go beyond dominant narratives and mainstream (social) media sources. Try to dig deeper into the local context, the underlying socio-economic causes of migration, and the structural issues faced by both migrants and host communities.

Strengthen your media literacy: encourage your friends, family, and yourself to read critically, question the sources, and recognise manipulation and ideology-based statements.

Hold authors accountable: demand transparency and responsibility from social media users, journalists, and media publishers who amplify disinformation for profit or other self-interested purposes.

This article was mainly written and based on research by Rachel Hierholzer, Simone Vogel, Alicia Cristobal, Sofia Bezorovaina, and Anna Toso. They did research on how immigrants are portrayed in the media for their project with Justice & Peace. Their findings can be found in this article. The original toolkit will be published on the Justice & Peace website.

Interesting reads

Migrant led media projects

MigraVoice: A cross-border community of experts with migration backgrounds participating in the creation of high-quality media content on European media.

SHIFT! Magazine: SHIFT! is a project of Re:Framing Migrants in the European Media that seeks to change currents on migrants and assure accurate, inclusive, and empowering representation. The magazine focus specifically on journalism and the newsroom and how to decolonise the newsroom with the subject of migration.

Organisations and projects

ON Migration: OnMigration is a guide for organisations with migration issues. They strengthen and connect professionals and organisations that are committed to the well-being of refugees and migrants.

Deep Canvassing Nederland: Deep Canvassing conducts door-to-door personal conversations about difficult topics in our divided society, like migration, to bridge the gap in polarizing debates and centre the human aspect to build a society in which everyone counts.

Dutch Council for Refugees: This organisation support refugees from the moment they are received in the Netherlands until they have found their own way. They also engage the public regarding the position of refugees in the Netherlands through public campaigns and highlight personal stories.

City Rights Radio: A podcast created by a social activist group of undocumented citizens of Amsterdam where discuss political matters and share their voices.

The story of Ashraf

Behind every headline, there is a human being. These are voices of people who have crossed borders not by choice, but by necessity; and who continue to shape their lives with courage, dignity, and hope.

Ashraf is a political refugee from Egypt and is currently studying and working to try to make a better life in the Netherlands. When asked about the portrayal of refugees in the media he talks about the double standards in the media. “If a refugee commits a crime, it’s everywhere. But if a Dutch person does, it disappears”. He emphasises that media stereotypes towards migrants and refugees often portray them as lazy or dangerous despite them trying to make a positive impact. He sees that refugees work, study, and are trying to engage in society. “Despite everything, I study, I work, I help others - I want to prove that I’m not just a statistic. I am a human being with dreams and skills.”

The story of Maryam

Maryam is a Kurdish refugee from Turkey who fled due to political oppression and threats to personal safety. She is passionate about human rights and social justice. She notes that when Kurdish people are portrayed at all, it's usually through a political or security lens - not as individuals with their culture and life stories. “I’m not just a refugee. I’m Kurdish. I’m a woman. I’m a person.”

She mentions that refugees just want to be treated and seen as human beings, not with pity. She criticises Dutch media for not fully acknowledging the diversity within refugee communities.

“We are all put into one box. But we all have different stories, struggles, and dream”

The story of Maxim

Maxim has a similar message, he wants people to see refugees as complex individuals — with contradictions, emotions, and creative ideas - not just victims or heroes. “We aren't stories of tragedy. We are stories of resilience, confusion, hope… all at once”.

Maxim is a Ukrainian refugee, former athlete, and creative individual with a reflective and philosophical outlook on life and identity. He is currently navigating integration and education. He wants to be seen not in charity ads, but in normal life - at school, at work, in creative spaces.

“Show me doing something ordinary. That’s the most radical thing.”

These stories remind us that migration is not about numbers or policies — it is about people. Real lives, real emotions, real futures. Let’s make space for those voices in every conversation.