Rise of criminality surrounding COA locations

The topic of refugee centres causes a lot of turmoil. When a proposal is made to open a new COA location, there is likely to be a protest against these plans. These protests can be effective and often stop the opening of new centres. Is that what is best for the neighbourhoods? What are the actual problems with the shelters?

The protests around COA locations are mostly held because people are scared that crimes will increase once a location is opened. These fears are genuine; people want to live in safe environments and feel safe in their homes. However, the fear that their environment will become less safe with a COA location is deceptive and informed by misinformation.

Although neighbourhoods with COA locations show slightly higher crime rates than the national average, research indicates that this is not caused by the presence of the centres. These areas already had elevated crime levels before the shelters were opened, and these patterns did not change after their arrival. In other words, the presence of a COA location does not appear to affect neighbourhood safety

You can read more about criminality rates among refugees in our article on the topic here.

As confirmed by a study “None of the analyses showed that the presence of a COA location has a demonstrable effect on the level of neighbourhood crime and on the individual propensity to become a victim of a crime. Furthermore, when distinctions are drawn by type of COA location, composition of the residents, and occupancy rates (an indicator of the average number of residents), no significant effects were found”.

Overcrowded shelters

While public debates often focus on the impact of COA locations on surrounding neighbourhoods, many of the challenges are found inside the centres themselves. The stories from the people I have interviewed about these centres are often quite distressing: sharing a living space with strangers who have also experienced trauma, having no certainty about the future, and having limited possibilities to work or settle in the unfamiliar country they have just entered.

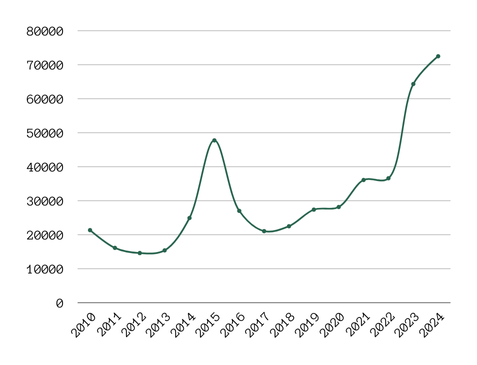

Amount of residents living in COA centres [source]

“You cannot go anywhere without permission. You are not allowed to work or to travel. And you’re scared, you’re still washing off the freshness of living a war”

Even though these living conditions in themselves are already ethically questionable, they have worsened over the past couple of years. Many refugees are living in (crisis) emergency centres for long periods, while these facilities are meant to host refugees only temporarily. Funding for the facilities was sparse, resulting in a worse living environment for asylum seekers. These emergency centres are dirtier, have improper beds, and create a system in which the residents have to move repeatedly to new centres. In 2022 , the Dutch court ruled that the shelters are detrimental to the inhabitants and failed to meet several European standards. Still, this is the ‘home’ for almost half of the asylum seekers living in the COA locations.

Currently, the COA locations are overcrowded and unable to provide decent living conditions. There are simply not enough shelters in the Netherlands for the amount of asylum seekers in need of shelters. This fact is sometimes used as an argument for why we should not allow more refugees to come to the Netherlands. This seems quite a logical thought. However, experts argue that it is essentially impossible to lower the amount of people seeking refuge in a country. Additionally, this overcrowdedness is not solely caused by new asylum seekers entering the Netherlands. The main source of insufficient accommodation is the financing of the COA and IND, which is based on inaccurate forecasts of how many refugees will enter the Netherlands. Furthermore, almost a third of the people staying in the COA locations already have a residence permit and should move to proper housing. However, the IND is behind on cases, creating a delay. This delay, along with the current housing crisis, means that status holders are stuck in overcrowded COA locations.

For a deeper look at the housing situation, including how refugees are assigned housing and how they influence the system, see our housing article here.

Health risks

The Health and Youth Care Inspectorate (IGJ) is a government organisation that keeps track of the living conditions of asylum seekers. In a recent study, they found that the living conditions for asylum seekers can be harmful for their health, especially for vulnerable groups like the elderly, children, people with chronic illnesses or disabilities, and pregnant women.

“It was very difficult living in the asylum centre. Because you have to live with people you don’t know. We had one toilet for nineteen people. There was no privacy”

The IDG found that many refugees have to stay in (crisis) emergency centres that are meant to be temporary. This means that refugees live with subpar facilities and living conditions. The use of emergency centres requires many refugees to move regularly to other COA locations. Being frequently relocated makes the continuity of care almost impossible. For vulnerable people, this can result in serious increases in health problems and worse care outcomes. For example, pregnant women in COA locations have quite a higher chance of dying due to their pregnancy than the average Dutch resident.

The IGJ study found similar issues in mental healthcare. Every time a refugee is relocated, they will be placed at the bottom of the waiting list of the new area. This lack of a stable living condition leads to incredibly long waiting times to get psychological support from the Dutch association for mental health and addiction care: the Nederlandse Geestelijke Gezondheidszorg (GGZ). Refugees are one of the most vulnerable groups to suffer from mental health issues. Besides, life in COA locations often strains asylum seekers’ mental health. Overcrowding, limited privacy, and the absence of support networks make mental stability difficult. Not getting proper care in time has many consequences, such as a further decline of conditions. It also heightens the pressure on the Dutch psychological care system, which is already quite strained with increasing waiting times, staff shortages, and a growing demand for care.

“The experience living in the asylum centre? It feels like you are not living on earth but on air. You have no documents, you are no one, you only have your memories”

Children in COA locations

The situation in refugee centres is not up to par for children. They have the right to a stable environment with privacy and safety. Yet, according to the IGJ, many children in COA locations do not have secure surroundings. They often lack privacy and experience a lot of turmoil and, in some cases, even unsafe conditions. Frequent relocations, due to the temporary nature of many refugee shelters, make the situation worse. According to the Convention on the Rights of the Child by the United Nations, every child has the right to life and development. The current state of COA locations does not comply with the agreements made in the convention, creating unjustifiably high risks of permanent damage for children and failing to uphold their universal rights.

"States Parties shall ensure to the maximum extent possible the survival and development of the child” - UN, OHCHR

The Distribution Law (De Spreidingswet)

The distribution law was adopted in February 2024 to address the problem of insufficient COA locations. The law makes it a legal duty for municipalities to house asylum seekers, increasing the number of permanent locations spread throughout the country, and decreasing the need for emergency accommodation. The division of shelters is based on the number of citizens and the prosperity of the municipalities.

In April 2025, the Dutch government proposed revoking the distribution law. The Advisory Council for Migration expressed concern about this resolution:

“The Council is concerned about the lack of justification, the fact that this plan is not carefully aligned with other measures and the fact that an instrument that appears to be working properly will be abolished without any operational alternatives returning in its place”

The COA also advises against this, stating that the distribution law is necessary for multiple reasons:

The report from the COA reveals that the distribution law is working well. It is creating new permanent COA locations that operate more humanely whilst saving money. The law is facilitating better organised accommodation distribution. This results in better facilities and residents having to move less frequently, which ultimately leads to better healthcare. Additionally, this promotes participation and contribution to society for asylum seekers.

There are currently not enough centres to accommodate the number of asylum seekers. This results in constant relocation, inadequate facilities, unstable environments for children, and a lack of support. Limited access to proper healthcare exacerbates the situation, underscoring the urgent need to improve conditions for residents, COA employees, care providers, and the healthcare system as a whole. Additional facilities could negate these issues by creating more stability, reducing maintenance costs, and improving the living conditions of the residents.

The story of Michael

Michael has been living in the Netherlands for three years, but he is still awaiting a decision on his residence permit. He enjoys working out, has a job in a restaurant in Zwolle, and dreams of one day inviting friends to his own home. Yet due to complications in his procedure, he still lives in a COA location.

Before coming to the Netherlands, a friend had described the asylum procedure to him, giving him the impression that he knew what to expect. The reality, however, was very different.

“She told me, ‘You’ll apply for asylum, they’ll find you a place to stay with others, and that’s it.’ But when I arrived, they sent me to Ter Apel. It was a tent with about 40 or 50 people, not a house. They told us it was because the Netherlands had no space left, everything was full of refugees. I couldn’t understand anything because I didn’t speak English. I was in a country where I didn’t know anything, and I was scared”.

He stayed there for 20 days before being moved to an emergency location in Rotterdam built from shipping containers. After that, he was transferred to the COA centre in Budel, nearly as large and chaotic as Ter Apel. Eventually, he was relocated to the asylum centre in Dronten, where he now shares accommodation with two other asylum seekers.

“I try to live a normal life. I do my best at work and with my friends. I try to be kind because it’s the people who make me a little happier”

His living situation remains difficult. Michael shares a room with an older man who struggles with severe mental health issues - slamming doors, banging pans, and screaming throughout the night. Instead of receiving proper care, the man remains in an asylum centre, and the COA appears unable to act.

“They comes to us and says, ‘We can’t do anything.’ The situation is draining.”

Michael wants a normal, peaceful life, but he often tries to avoid being at the centre. Despite everything, he remains hopeful and tries to focus on the positive people around him.

“When I’m home, I just sleep until the next day. And when I’m free, I go to the gym, I go shopping - I prefer to stay busy”.